By David Cohea

Climbing above 10 thousand feet, you reach for an oxygen mask, knowing that the plane will climb a lot higher en route to its daily target. Outside, it’s 60 degrees below zero. You wear what protection you can against the cold – an electrically heated suit, heavy gloves.

You also wear a 30-pound flak suit and steel helmet—protection against antiaircraft fire that’s sure as rain to come.

No way you can work and wear a parachute, so you wear the parachute harness and hope when its necessary you can get to your chute in time.

Outside the window, you see dozens of B-17 bombers all around you. It’s an eight-hour round trip fraught with peril. Not all of you will return. And your chances of completing all 25 missions of your tour of duty are only about one in four.

It’s 1944, and you know you’re a long, long way from home.

* * *

space

The B17 was a strategic bomber flown by the US Air Force during much of the Second World War against German targets, a 4-engined behemoth capable of flying long distances and somehow keeping aloft despite taking heavy damage from German air and ground defenses.

Its 9-man crew consisted of a pilot, air commander, bombardier, 2 navigators, 4 gunners manning the top turret, tail, waist and ball turret guns, and a radio operator. They flew wearing oxygen masks and were bundled up against the cold of flying at up to 29 thousand feet.

Flying to their targets in the industrial heartland of Germany (seeking to derail the military output of the Reich), B17s flew in formations of 18 planes scattered at three altitudes, linking with two other 18-plane formations to form a wedge of destruction a mile and a half wide. (Later the formation was changed to a more defensible formation of three groups of 12) Each plane carried a payload of about 2 tons of bombs; at the peak of the air war in November 1944, some 35 thousand tons of bombs would be dropped.

German defenses were strong. Since they were fighting over their homeland, the FW-190 and ME-109 fighter pilots could run multiple missions in a day. A pilot could be shot down in one plane and return in another in hours. Flak guns were numerous and powerful and a single shell hitting the right place could send a bomber plummeting to its destruction.

To defend themselves, the total combat box of the B-17 formation would carry some 640 50-caliber guns each capable of firing 14 rounds a second to a distance of 600 yards. Still, the cost was heavy. On October 17-18, 1944 some 300 attacking Fortresses were met by an equal number of German fighter planes of the Luftwaffe and some 90 Fortresses were shot down; 800 crew members died.

Later in the war, American P-51 Mustang and P-47 Thunderbolt fighter planes that could fly the distance along with the Fortresses greatly reduced the casualty rate, but in flying in a B17 was dicey business, dicey indeed.

* * *

space

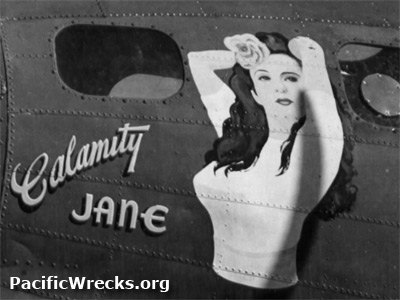

American military hardware was good as far as it went, but how to ensure a safe return? B17 crew members took extra measure to woo Fate as best they could, painting the noses of the aircraft with animals, cartoon characters, and, most usually, with women, sometimes clothed, sometimes not so clothed, usually young and marriageable, often named after wives and girlfriends back home.

Hoping it would boost aircrew morale, Air Force commanders tolerated the practice. The U.S. Navy, by contrast, prohibited nose art in the Pacific Theater; planes were simply painted with their numbers.

Much like ships of old, B17 bombers were given names and figureheads to personalize them and imbue them with that extra bit of added mojo. Maybe a pretty lady painted on the fuselage did no more than provide a visual reminder to crews than giving the crews a reason to fight their way through hell and back.

Maybe they personified those haunting voice on Armed Forces Radio sounding like a loved one back home, something angelic and pure and untouched by war. And maybe they were indeed angels, seeing to it that they made it back to base and provided blessing for the next day’s sortie and the next … Until that dreamed-of day came when an airman could fly at last to the real little lady back home.

At the height of the war, nose-artists were in very high demand. Professional civilian artists as well as talented servicemen would do the work. Tony Starcer was the resident artist for the 91st Bomb Group and painted some 217 bomber noses. Pin-up by illustrator Alberto Vargas published in Esquire magazine were a favorite of B17 nose painters.

The art was daring to a point — there was always the threat of censorship from Air Force brass — but the accent of curves may have been part of the unconscious association with the Beloved and the fragile hulk of the B17 fuselage, something all too penetrable without the valiant efforts of the crew.

Too often the crews would go down with their ladies. And yet, despite odds hugely to the contrary, some B17s and their crews would fly out again and again and again, dropping their payloads, surviving the withering fire of German defenses and make it back to the home field until it was time to go all the way home.

* * *

space

One of these was the Memphis Belle, A B17-F of the 324 Bomb Squadron that flew out of Bassingbourne, England. The ship was supposed to be named after pilot Robert Morgan’s sweetheart back in Memphis, nicknamed Little One. But one night he and his copilot Jim Verinis saw the movie Lady For a Night in which the lead character owned a riverboat named the Memphis Belle, and that became the B17’s handle.

Morgan then wrote artist Charles Petty care of Esquire magazine for a pinup to paint on the fuselage, and Petty supplied one from the magazine’s April 1941 issue. Tony Starcer painted the image on both sides of Memphis Belle’s fuselage, with Belle in a blue suit on the port side and a red suit on the starboard.

space

space

Memphis Belle was the first B-17 to complete 25 missions with her crew intact. The aircraft was flown back to the United States in 1943 to fly on a 31-city war bond tour. After the war, the Memphis Belle was saved from reclamation mostly by the efforts of Memphis mayor Walter Chandler, and the city bought the plane for $350. She sat out-of-doors deteriorating into the 1980s, with every removable piece of equipment pried loose by scavengers.

In 2005, the National Museum of the United States Air Force acquired the Memphis Belle and is in the process of a lengthy restoration. Nearly 70 years after she steered her crew through every flak and bullet thrown at them by the War, the Belle is still around, and her figurehead is still turned away from us, sighting a way home.

space

space

space

space

space

space